Picturing the Trinity: Rublev’s icon and the myth of East/West divisions

At the recent annual meeting of the Tyndale Fellowship Doctrine Study Group, a number of people were kind enough to offer responses to my recent book on the Trinity. I thoroughly enjoyed the interaction, and came away with a number of things to think about. One concerned the iconography of the Trinity.

There is a famous story, which I have told myself on occasion in the past, of how the different ways of depicting the Trinity in Eastern and Western Christian art demonstrates the different doctrinal emphases that the two traditions developed. The Eastern tradition is identified with Rublëv’s icon of the Holy Trinity, pictured above. It is a depiction of the three angels who came to visit Abraham and Sarah at Mamre (Gen. 18) the image shows three deliberately androgynous figures of equal majesty, united by their shared gaze, seated around a table on which the Eucharistic elements are spread. This is supposed to show the Eastern tradition of Trinitarian theology: beginning in the gospel story, we speak of three divine Persons united in a communion of love. The standard Trinitarian image in the Western tradition, by contrast, looks like this:

The Father, depicted as an elderly bearded man, sits enthroned, holding the crucified Son; the Holy Spirit is present in the form of a dove, sometimes hovering overhead, here also held by the Father. The implication seems clear: the Father is truly divine, the Son and Spirit somehow closely related, but not truly divine. The gospel story is something acted out by the minions – angels? – of the true God, the Son who is crucified and the Spirit who comes as a dove; the true God sits enthroned above the fray.

Now, my concern here is not about which is a more adequate depiction of the Trinity – or whether any depiction of the Trinity can be in any way adequate; rather, I am interested in the claim that the history of Christian art demonstrates vividly a basic difference in Trinitarian doctrine between East and West. I argued in my book on the Trinity that no such difference exists, and so it would be something of an embarrassment to me if it could be shown so easily from art history. Can the story I have told above be unpicked?

Let me start with Rublëv; his icon can be dated with confidence to early in the fifteenth century – conjectured dates vary between 1408 and 1427. This is quite late on in history, and an obvious question is, what (if any) depiction of the Trinity was common in the Eastern church before 1400? The answer would seem to be that icons of the Trinity were not common, but where they were painted, they almost universally showed the Father as the Ancient of Days, enthroned and white-bearded, with the Son as the infant Jesus cradled on his lap, and the Spirit as a dove. More common are variations on this theme: this Trinitarian image being inserted into the upper corner of an icon of a saint, or similar. One famous, and interesting, example, is the Theokotos of Kursk, an icon famed in popular devotion for its miracles.

This is a standard Theotokos (‘Mother of God’) icon, showing the Blessed Virgin with the infant Christ on her knee; around the main panel are nine saints, and (centre top) the Father, depicted as the Ancient of Days, with the Spirit as a dove in the centre of his chest. It seems that the Father – infant Christ – Spirit as dove imagery was, by the thirteenth century (when the Theotokos of Kursk was probably painted), sufficiently well-known to be alluded to, modified, almost ‘played with’ (although there is little sense of play in formal iconography, of course).

The ‘Ancient of Days’ style Trinity icon became popular after the middle of the fifteenth century; in Russia, the Synod of Moscow, 1667, banned the style because it invented an image for the Father.

Is there pre-history for the ‘angels at Mamre’ style of Trinitarian icon? There is. A mould found near Jerusalem, and dated to the fifth century, has the three angels on one side and a female figure (described as a ‘goddess’ in art catalogues; I take it that it was intended to be the Blessed Virgin, although there is some evidence of syncretic religious practices in Palestine in the fourth century). This mould might have been used for making shaped cakes, or perhaps medallions of some sort, for pilgrims, indicating that the image was already popular. (Details, and images, of the mould can be found in Kurt Weitzmann’s catalogue to the 1977-8 MMA exhibition, Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Art, pp. 583-4.)

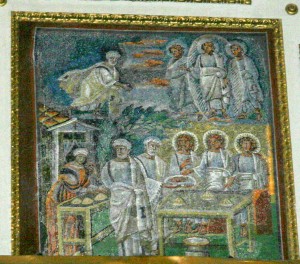

The mould has no direct reference to the angels being identified with the Trinity, however; for the earliest examples of this we need to look a little earlier, but not to the East but to Rome. There are several examples: a painting on a catacomb wall on the Via Latina, dated to the fourth century; various carvings on Christian sarcophagi; and an early fifth-century mosaic in Sta Maria Maggiore, Rome.

Mosaic of Abraham at Mamre from Sta Maria Maggiore, Rome, c.425 (image from Vanderbilt Divinity School website, licensed under GNU CC licence)

This image is complex – Abraham appears three times, for example. The artist deployed a ‘continuous narration’ technique, depicting several scenes of the story in one panel. So at the top Abraham greets the three angels, and then at the bottom to the left requests Sarah to prepare food, which he serves to the angels in the bottom right scene. The iconography is slightly ambiguous: in the upper panel, the middle figure seems to have a mandorla (full-body halo), which is absent from the lower image. The mandorla later became standard in depictions of Christ, and it is possible to read it here as a reference back to Justin Martyr’s interpretation of the story of Mamre as Christ appearing, flanked by two angels. The lack of a mandorla in the lower panel, and the fact that this would be a very early example of the use, leads me to suspect that this is an overinterpretation, however; the imagery is of the Trinity.

There are other aspects of the history of art to be considered: the style, common East and West, of the Father as Ancient of Days and Christ seated on two thrones with the Spirit as dove hovering between; the Western styles of three identical enthroned figures, or a three-faced deity. My point, however, is that a simple claim that the assumption that the Western tradition pictures God as the enthroned Father cradling Jesus, whereas the Eastern tradition deploys a much more equal/relational image, is not supported by the evidence. The claim that this difference in art is indicative of a difference in theology is simply untenable.

Thanks Steve,

It is very interesting to see the various icons, and I wholeheartedly agree with your conclusions. I am glad that you enjoyed the conference, I know that a number of us felt it was the best one that we have had in recent years.